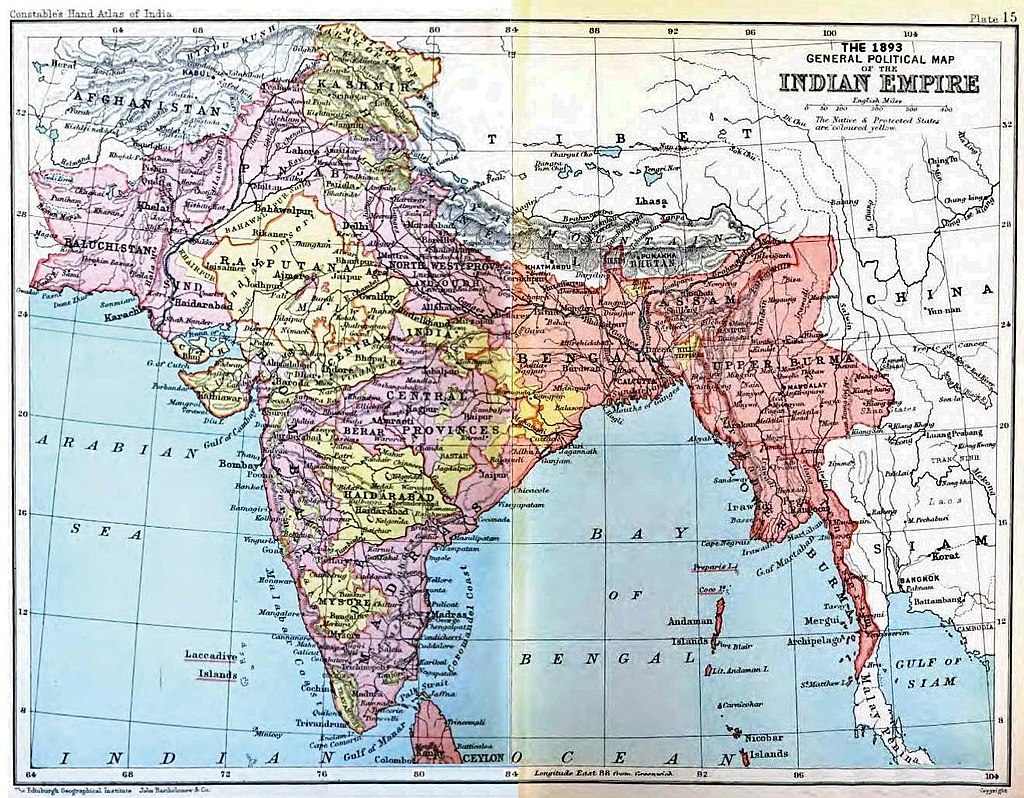

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged from Bengal. It later took root in the newly formed Indian National Congress with prominent moderate leaders seeking the right to appear for Indian Civil Service examinations in British India, as well as more economic rights for natives. The first half of the 20th century saw a more radical approach towards self-rule.

The stages of the independence struggle in the 1920s were characterized by the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi and Congress’ adoption of Gandhi’s policy of non-violence and civil disobedience. Some of the leading followers of Gandhi’s ideology were Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel, Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Maulana Azad, and others. Intellectuals such as Rabindranath Tagore, Subramania Bharati, and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay spread patriotic awareness. Female leaders like Sarojini Naidu, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, Pritilata Waddedar, and Kasturba Gandhi promoted the emancipation of Indian women and their participation in the freedom struggle.

Few leaders followed a more violent approach, which became especially popular after the Rowlatt Act, which permitted indefinite detention. The Act sparked protests across India, especially in the Punjab province, where they were violently suppressed in the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

The Indian independence movement was in constant ideological evolution. Essentially anti-colonial, it was supplemented by visions of independent, economic development with a secular, democratic, republican, and civil-libertarian political structure. After the 1930s, the movement took on a strong socialist orientation. It culminated in the Indian Independence Act 1947, which ended Crown suzerainty and partitioned British Raj into Dominion of India and Dominion of Pakistan.

India remained a Crown Dominion until 26 January 1950, when the Constitution of India established the Republic of India. Pakistan remained a dominion until 1956 when it adopted its first constitution. In 1971, East Pakistan declared its own independence as Bangladesh.

By 1900, although the Congress had emerged as an all-India political organisation, it did not have the support of most Indian Muslims. Attacks by Hindu reformers against religious conversion, cow slaughter, and the preservation of Urdu in Arabic script deepened their concerns of minority status and denial of rights if the Congress alone were to represent the people of India. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan launched a movement for Muslim regeneration that culminated in the founding in 1875 of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh (renamed Aligarh Muslim University in 1920). Its objective was to educate students by emphasising the compatibility of Islam with modern western knowledge. The diversity among India’s Muslims, however, made it impossible to bring about uniform cultural and intellectual regeneration.

The Hindu faction of the Independence movement was led by Nationalist leader Lokmanya Tilak, who was regarded as the “father of Indian Unrest” by the British. Along with Tilak were leaders like Gopal Krishna Gokhale , who was the inspiration, political mentor and role model of Mahatma Gandhi and inspired several other freedom activists.

Nationalistic sentiments among Congress members led to a push to be represented in the bodies of government, as well as to have a say in the legislation and administration of India. Congressmen saw themselves as loyalists, but wanted an active role in governing their own country, albeit as part of the Empire. This trend was personified by Dadabhai Naoroji, who went as far as contesting, successfully, an election to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, becoming its first Indian member.

Dadabhai Naoroji was the first Indian nationalist to embrace Swaraj as the destiny of the nation. Bal Gangadhar Tilak deeply opposed a British education system that ignored and defamed India’s culture, history, and values. He resented the denial of freedom of expression for nationalists, and the lack of any voice or role for ordinary Indians in the affairs of their nation. For these reasons, he considered Swaraj as the natural and only solution. His popular sentence “Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it” became the source of inspiration for Indians.

In 1907, Congress was split into two factions: The radicals, led by Tilak, advocated civil agitation and direct revolution to overthrow the British Empire and the abandonment of all British goods. This movement gained traction and huge following of the masses in the western and eastern parts of India. The moderates, led by leaders like Dadabhai Naoroji and Gopal Krishna Gokhale, on the other hand, wanted reform within the framework of British rule. Tilak was backed by rising public leaders like Bipin Chandra Pal and Lala Lajpat Rai, who held the same point of view. Under them, India’s three great states – Maharashtra, Bengal and Punjab shaped the demand of the people and India’s nationalism. Gokhale criticised Tilak for encouraging acts of violence and armed resistance. But the Congress of 1906 did not have public membership, and thus Tilak and his supporters were forced to leave the party.

But with Tilak’s arrest, all hopes for an Indian offensive were stalled. The Indian National Congress lost credibility with the people. A Muslim deputation met with the Viceroy, Minto (1905–10), seeking concessions from the impending constitutional reforms, including special considerations in government service and electorates. The British recognised some of the Muslim League’s petitions by increasing the number of elective offices reserved for Muslims in the Indian Councils Act 1909. The Muslim League insisted on its separateness from the Hindu-dominated Congress, as the voice of a “nation within a nation”.

The Ghadar Party was formed overseas in 1913 to fight for the Independence of India with members coming from the United States and Canada, as well as Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Members of the party aimed for Hindu, Sikh, and Muslim unity against the British.

Click here to access more info and explore further.